Formal Culture thesis paper: butlers_fc07 (1.7MB)

Is it really about the machine? We do distinguish between machines and representations? Our machines are invisible. And what about contexts? The context here was too obvious and lacking contrast. Writing in a cubicle needs to be contrasted with writing in the wilderness.

“And out of the hills came a strange thing.

It was a machine like a jade-green insect, a praying mantis, delicately rushing through the cold air; indistinct, countless green diamonds winking over its body, and red jewels that glittered with multifaceted eyes. Its six legs fell upon the ancient highway with the sounds of a sparse rain which dwindled away, and from the back of the machine a Martian with melted gold for eyes looked down at Tomás as if he were looking into a well”

This quote from Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles is from Peter Courtemanche, http://absolutevalueofnoise.ca/ to show some sculptures in the next show at the Ellen.

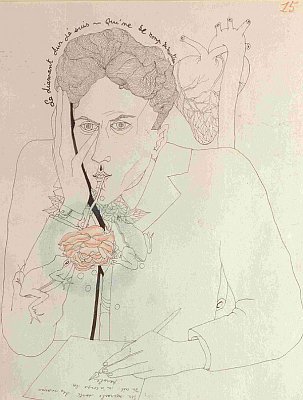

Hanne Darboven

Published April 30, 2007 ethnography , observed , paper , poetry , thoughts , Uncategorized Leave a CommentEcrivez Legiblement

Published April 29, 2007 observed , paper , poetry , thoughts , Uncategorized 2 CommentsWho argues that drawings are actually more effective forms of representation (over photographs), for what distinctive elements they capture? There certainly would have been a school for that thought, wouldn’t there? Alfred Stieglitz wrote about photography as art, Muybridge: photos for science. But before that it was magic, right? There must have been guilds whose professions were threatened, draftsmen, portrait and landscape painters.

Although Maya Deren does do a wonderful job representing dreams in film.

The Assassination of Joan Lee by Unknown Forces, by Ben Lee

is his ethnography devoted to her

Thoughts about a Thesis about Writing

Published April 29, 2007 thoughts , Uncategorized Leave a Comment The installation, my first, is concretising more than I imagined. I had been reading and writing in preparation: developing plans, hypotheses, while the most important elements are taught by the contexts of the work. For example, while I was inspired by Cornelia Parker’s 1991 Cold Dark Matter — An Exploded View (pictured here), I am finding the metaphysics of ideas more implosive. Cubicles may tend more to collapse into themselves. Becoming immense in their magnifications. I wouldn’t know. At least in this case. Office furniture seems to organize itself neatly in any configuration. A messy Tetris board, the chaos of a Rubix cube. At least when all of the contents have been concealed. In the writing I’ve asked so often “Is it important that this mean?” Now I am totally bent on preserving the words. So, yes. My answer is yes. It is important that writing mean. Purely subjective. Nonetheless it does mean more than it means, as we all know.

The installation, my first, is concretising more than I imagined. I had been reading and writing in preparation: developing plans, hypotheses, while the most important elements are taught by the contexts of the work. For example, while I was inspired by Cornelia Parker’s 1991 Cold Dark Matter — An Exploded View (pictured here), I am finding the metaphysics of ideas more implosive. Cubicles may tend more to collapse into themselves. Becoming immense in their magnifications. I wouldn’t know. At least in this case. Office furniture seems to organize itself neatly in any configuration. A messy Tetris board, the chaos of a Rubix cube. At least when all of the contents have been concealed. In the writing I’ve asked so often “Is it important that this mean?” Now I am totally bent on preserving the words. So, yes. My answer is yes. It is important that writing mean. Purely subjective. Nonetheless it does mean more than it means, as we all know.

An art work employed to explore writing, discovers realms beyond words.

Equally satisfying is the confirmation that writing is promonotory, of course, I mean “premonitory”, but it’s an alright allegory. The matter of my exploration contains the answers. I wanted to know about the constructs of bureaucracy, (and I’m tracking down accounts payable), creativity and globalization (and all of the texts point to art writers, critics, scholars and artists’ stories, stories, statements, letters, diaries,), and the shapes of aluminum filing cabinets, papers and hands in the process of writing one word at a time have things to say about it. Does writing find itself within the cabinets, or from climbing atop them?

Be just and if you can’t be just, be arbitrary.

William S. Burroughs

I’ve said in the past I like to do a credit sequence that segues the audience from their real life into the life of the movie.

David Cronenberg

In Naked Lunch the intro credits are shadows in some 1990’s take on 1950’s film noir, revealed by passing sheets of yellow, blue, red, purple and green as they slide across the screen horizontally then vertically, to the tune of an orchestral backed-saxophone, led by red stripes. The font is blocky, sans serif, all caps yet irregular, some letters appearing smaller and underlined, while other letters are bulging bold, others are thin and contracted. Bill Lee so totally reminds me of Joseph Beuys — coincidence?! There is no narrator per se. The point of view revolves around Lee: his experiences as an agent with his case officer (the ever-changing writing tool, that reports to his controller). I’m confused whether I relate more to William or Joan. While she writes long-hand: shooting up with yellow powder for a Kafka-high, he writes with a Clark Nova, smothering pressure points (and Joan) with this black, inky, stuff. His writing happens in his absence. It is a demonstration of so much of what I’ve been reading in Cixous. But the Colours!

When Fadela destroys the machine that the Lees use to make love through Arabic writing:

“Well that’s it then, the woman has got to go”.

They discover in the roots of a plant: “Well, this is how Fadela’s been controlling you Joan: your blood, your pubic hair and your finger nails!”

Joan says “Fadela controls no body and you know it. You enforce control upon her…Poor woman’s probably desperate to get out of our household.”

“I think we ought to only read the kind of books that wound and stab us. If the book we are reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us. That is my belief.

He wrote this letter because his friend reproached him for not having answered his letters. Kafka answers him by saying: excuse me, but I was reading (17).

Hélène Cixous

Three steps on the Ladder of Writing, 1993

Natasha Morley (left) and Jessie Winter Mudie in Kissed, 1996

I would like to transcribe more from Cixous, except that I wouldn’t know where to stop. Her writing is so incredibly whole. There are no preexisting segments. No parts. I would inevitably wind up keying in the whole book.

“What do we do with the other when we create? What does the author do? What does the painter do? That is, what do we do? This is our portrait, the portrait of the artist done by himself or herself, the portrait of you by me: it is oval: the Egg of Evil. What do we do with the body of the other when we are in a state of creation — and with our own bodies too. We annihilate (ourselves) (Thomas Bernhard would say), we pine (ourselves) away (Edgar Allen Poe would say), we erase (ourselves) (Henry James would say). In short, we institute immurement. It all begins with walls. Those of the tower. Those of the chateau we enter as we follow a seriously wounded narrator. ‘The Oval Portrait’ starts like this: (27)

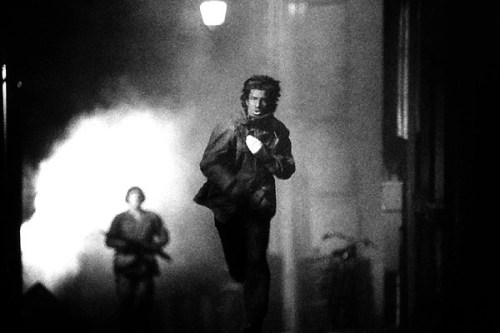

The Emancipated Spectator w/Amants Réguliers inserts

Published April 25, 2007 observed , paper , poetry , thoughts Leave a Comment“The collective power that is common to these spectators is not the status of members of a collective body. Nor is it a peculiar kind of interactivity. It is the power to translate in their own way what they are looking at. It is the power to connect it with the intellectual adventure that makes any of them similar to any other insofar as his or her path looks unlike any other. The common power is the power of equality of intelligences. This power binds individuals together to the very extent that it keeps them apart from each other; it is the power each of us possesses in equal measure to make our own way in the world. What has to be put to the test by our performances — whether teaching or acting, speaking, writing, making art, etc. — is not the capacity of aggregation of a collective but the capacity of the anonymous, the capacity that makes anybody equal to everybody. This capacity works through unpredictable and irreducible distances. It works through an unpredictable and irreducible play of associations and dissociations.

“Associating and dissociating instead of being the privileged medium that conveys the knowledge or energy that makes people active — this could be the principle of an ’emancipation of the spectator’, which means the emancipation of any of us as a spectator. Spectatorship is not a passivity that must be turned into activity. It is our normal situation. We learn and teach, we act and know, as spectators who link what they see with what they have been told, done and dreamed. There is no privileged medium, just as there is no privileged starting point. Everywhere there are starting points and turning points from which we learn new things, if we first dismiss the presupposition of distance, second the distribution of roles, and third the borders between territories. We don’t need to turn spectators into actors. We do need to acknowledge that every spectator is already an actor in his own story. We needn’t turn the ignorant into the learned or, merely out of desire to overturn things, make the student or the ignorant person the master of his masters (278-279).

“I am aware that all this may sound like words, mere words. But I wouldn’t take that as an insult. We’ve heard so many speakers pass their words off as more than words, as passwords enabling us to enter a new life. We’ve seen so many spectacles boasting of being no mere spectacles but ceremonials of community. Even now, in spite of the so-called postmodern skepticism about changing the way we live, one sees so many shows posing as religious mysteries that it might not seem so outrageous to hear, for a change, that words are only words. Breaking away from the phantasms of the Word made flesh and the spectator turned active, knowing that words are only words and spectacles only spectacles, may help us better understand how words, stories, and performances can help us change something in the world we live in”(280).

“Emancipation can’t be expected from forms of art that presuppose the imbecility of the viewer while anticipating their precise effect on that viewer: for example, exhibitions that capitalize on the denunciation of the ‘society of the spectacle’ or of ‘consumer society’ — bugbears that have already been denounced a hundred times — or those that want to make viewers ‘active’ at all costs with the help of various gadgets borrowed from advertising, a desire predicated on the presupposition that the spectator is otherwise rendered ‘passive’ solely by virtue of his looking. An art is emancipated and emancipating when it renounces the authority of the imposed message, the target audience, and the univocal mode of explicating the world, when, in other words, it stops wanting to emancipate us” (258).

Jacques Ranciére, in conversation with Fulvia Carnevale and John Kelsey in Artforum (march 2007)

Les Amants Réguliers* * * * *